A pastor at my church, Steve Treichler, recently shared, “People do that which is fun.” Though he was instructing on leadership-building qualities and how to get community members to engage, the same pithy insight applies in the classroom: If you want your students to be engaged, make it fun. Effective teachers know good writing instruction must include explicit, academic tasks, but if personalization and fun are absent from writing, we will quickly lose our students. Having fun not only increases engagement, it builds relational bonds, crafts memories, produces more resilient children, and, ultimately, results in kids enjoying school and learning.

As a current first grade teacher who has taught a range of elementary grades, I recognize that teachers today are faced with more pressure than ever. When faced with a shortage of time and a heavy load of standards, unfortunately, writing is often cut first for the sake of time. There is too much at stake if we lose budding, creative, unique writers and thinkers to a diet of only academic, serious writing, or cut it out altogether. In the name of joy, I make a case here to elevate practices of writing for authentic audiences, playing with words, and celebrating together.

Involving Others

Writing is an inherently social activity contrary to the mental image of a student writing independently at their desk. Partner writing, sharing published writing, and authentic audiences are an easy onramp to engage students in social, joyful, purposeful writing. Sharing writing builds teamwork and the writing community by allowing students to listen and learn from each other, take risks, give feedback, and exchange praise.

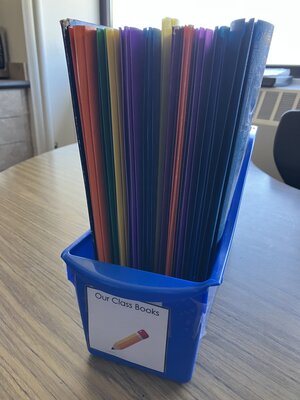

Each year, I compile finished writing projects into class books that are available in the classroom library, which thereafter brings weeks of enjoying friends’ writing, all while fostering connections as classmates. Around each Valentine’s Day, I introduce letter writing to authentic audiences, which includes sending letters to people around school. This links writing to a meaningful purpose: To connect with those you care about. Writing a thank-you note to a cafeteria worker or setting up a classroom mailbox for letters to classmates goes a long way toward building students’ writing agency and excitement that their writing has the potential to brighten someone’s day.

Writing as Play

Beyond summaries, paragraphs, and essays, students need opportunities to laugh, make mistakes in a silly way, and stretch creative muscles in writing if we ever expect them to return on their own. Using mentor texts as a model for playful ideas is a surefire way to prime the pump of joy and creativity in young writers. After reading some excerpts from books like

Scranimals by Jack Prelutsky or

If You Give a Mouse a Cookie by Laura Numeroff, students get carried away in their own story creations modeled after a wonderful, out-of-the-box structure. A colleague even created an “If You Take a Mouse to School” home-to-school class book bag with a notebook and mouse stuffed animal (pictured above) to send home to families for the chance to continue the mouse’s adventure outside of the writing block by creating their own pages.

From tying in games like Telestrations, where a small group alternates drawing and writing sentences, during indoor recess, to writing nonfiction facts as riddles to guess the object, to using silly words from a word bank to make poems, there are many simple writing activities that leverage fun. These are powerful, low-prep experiences that model to students we do not only write for academic purposes, but because writing allows us to think in new ways, bonds us together, and makes us laugh. Ultimately, we write because we enjoy it.

Celebrating

Finally, one of the best ways to create a culture of writers and ensure joy is to celebrate! Writers need to know that their work and thinking are celebrated, and worthy of shared delight. Often in my classroom, I elevate sharing at the end of a unit by the practice of the author’s chair, zhuzhed up with a red curtain projected on my screen. Intermediate elementary students love the prop of a microphone. After particularly satisfying journeys through the writing process, our class celebrates with a publishing party, complete with apple juice and popcorn to cheers each writer after they share in a small group of three to four peers. This celebratory sharing can also be modified to fit in a couple students at a time during morning meeting or closing circle, followed by finger snaps of recognition.

Young writers deserve to experience joy, choice, and delight in writing if we expect them to share their thoughts beyond academic contexts and develop as thinkers and word lovers. Though writing does give us the skills to summarize and convey the main ideas of what we learn, to sever the craft from personal expression and reflection is doing a disservice. Students are academic learners, but they are also thinkers and feelers who must experience writing socially and joyfully if we ever expect them to write with their authentic voices throughout their lives. And isn’t the goal for children to use writing to tell someone they care, to bring about change in their communities, and to inspire joy no matter where life takes them?

As a teacher who faces the Tetris puzzle of fitting in all of the academic demands, I urge teachers not to neglect the necessity of writing for fun. With some brainstorming, we can take simple steps to craft our students’ attitudes about writing to be social, playful, and celebratory in ways that keep young writers eagerly picking up their pencils with a smile.